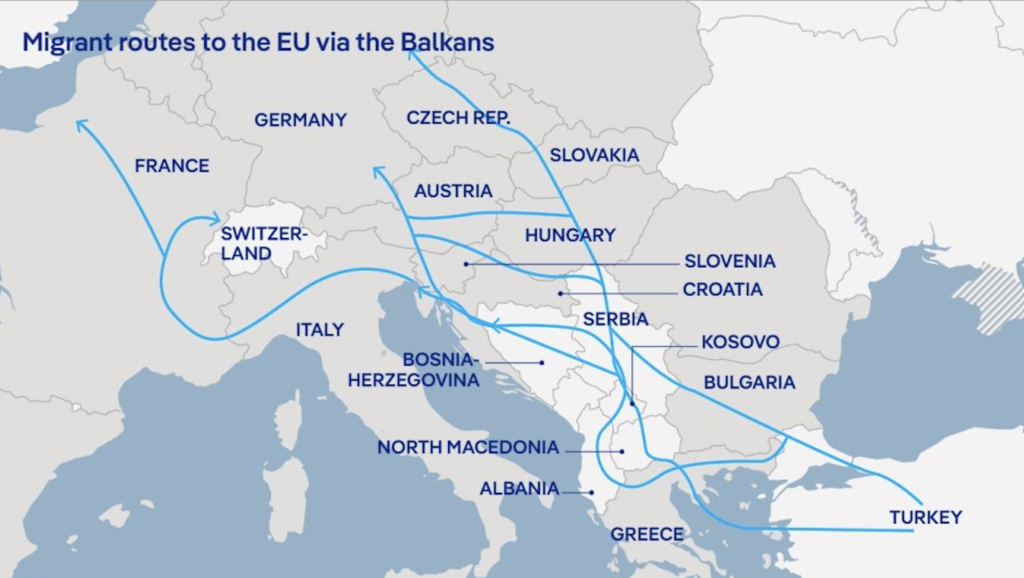

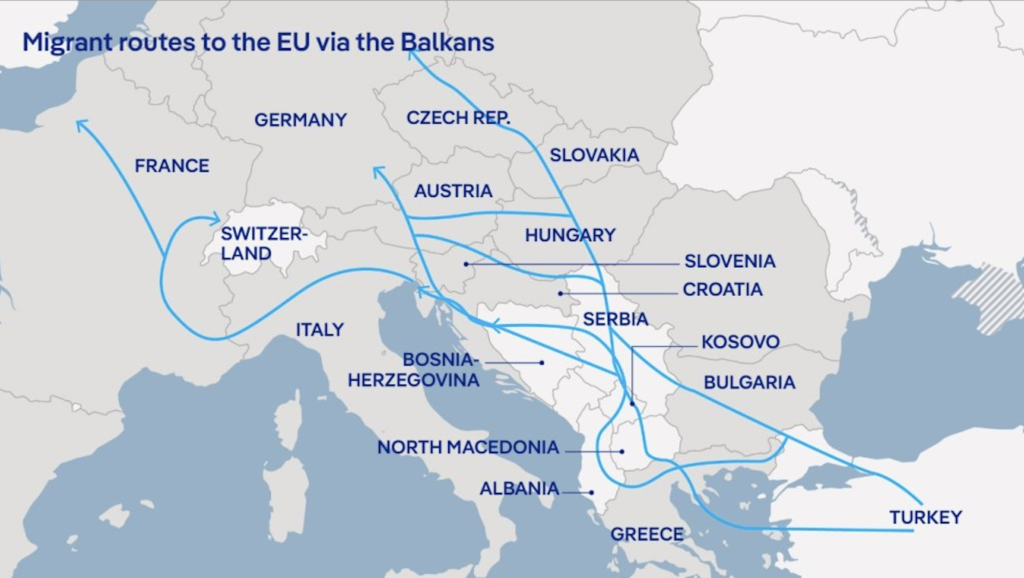

In the shadows of forests and at the edges of European borders, a human crisis unfolds—one that goes far beyond fleeing war or poverty. As EU border policies grow increasingly restrictive, the Balkan migration route has transformed into a dangerous corridor controlled by sophisticated smuggling networks.

Migrants are forced to rely on ruthless traffickers, paying a heavy price—sometimes in money, sometimes with their freedom or lives. With minimal state protection and dwindling institutional support, the journey to safety has become a high-risk game of survival.

Research team

Along the Balkan route migration has become increasingly controlled by criminal networks. More and more smugglers appear to be exploiting restrictive EU border policies and subjecting migrants to extortion and abuse. While NGOs provide some support, the lack of coordinated protection and institutional challenges leave migrants vulnerable to exploitation along the route.

In the borderlands of Serbia, Bosnia and Hungary, the migration ecosystem is constantly evolving. As European Union border policies grow increasingly restrictive, migrants are being pushed into more dangerous and clandestine routes controlled by sophisticated criminal networks, think NGOs who work with migrants along the routes.

The closure of border camps has not halted migration in this region, instead, it has transformed it into a high-stakes underground operation.

Milica Švabić, from the organization KlikAktiv (a Serbian NGO developing social policies), explains that “unfortunately, more and more refugees are reporting abductions, extortions, and other forms of abuse by smugglers and criminal groups in the previous months.” She notes that groups of Afghan smugglers are currently operating both on the Serbian-Bosnian border and the Serbian-Hungarian border. KlikAktiv has been collecting testimonies of abuses committed at both borders.

Changing landscape of smuggling networks

The migration landscape in Serbia has dramatically shifted. Where makeshift camps once dotted the border regions, now migrants are hidden in private apartments across urban centers, moved under cover of darkness. Afghan criminal gangs and local networks have seized control, creating an elaborate smuggling infrastructure that operates beyond institutional oversight. These networks have adapted to restrictive border policies, turning human movement into a complex logistical challenge that prioritizes secrecy over safety.

Švabić tells InfoMigrants that the NGO has also documented “cases of refugees being abducted and kept in isolated locations (usually private apartments or houses) until their family pays a ransom for their release.” This ransom often goes up to several thousand euros, she adds.

These testimonies are echoed in a recent investigation by the regional news platform Balkan Insight BIRN. In a recent report, they uncovered how BWK members, (a notorious Afghan gang operating in Bosnia) have held asylum seekers hostage in forest camps, demanding ransoms from relatives while subjecting them to horrific abuse, reportedly including rape and physical torture. Sometimes, these acts are filmed and sent to families as proof of life.

Rados Djurovic, the director of Serbian NGO Asylum Protection Center, notes too that smugglers are using private apartments and hidden locations in large urban areas to hide people, mistreat them, and organize border crossings. “These operations have become increasingly violent as smugglers use force to enforce their control and extract bribes. They kidnap people, hold them in these flats, and extort money from their families abroad,” he says.

Other rights groups and migration experts have reported similar cases, indicating that this violence is widespread along the Balkan Route. Roberto Forin from the Mixed Migration Center (MMC) states that a recent report by the organization titled “Mixed migration in the Western Balkans” documents a range of abuses and protection risks faced by migrants and refugees, including robbery, physical violence, and extortion. He points out however, that “it does not specifically identify armed groups of Afghan origin as perpetrators. However, respondents frequently reported being targeted by smugglers and criminal networks, sometimes involving violence and coercion.”

The impact of border policies and pushbacks

Many rights groups argue that the increased security measures are partly responsible for this evolution in the situation, because they essentially force migrants to rely more heavily on smugglers, because due to increased controls, border crossings have become more difficult to navigate, pushing migrants into increasingly dangerous situations.

A spokesperson for the Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN) stated that in their view “the appearance of such groups is simply the consequence of the growing securitization of border regions throughout Europe. As European border regimes deploy increasingly violent methods to prevent migration, migrants are left with no other choice but to rely on informal methods to cross borders.”

BVMN added that ultimately, “it is people on the move who bear the lion’s share of the violence, whether at the hands of state authorities or the very groups that claim to help them on their journey.”

Several experts and rights advocates also draw a clear connection between restrictive border practices and the increasing reliance on smugglers.

Forin warns that “border violence and restrictions exacerbate migrants’ vulnerability to exploitation and abuse. Pushbacks often force individuals to take more dangerous routes and rely on smugglers, increasing their exposure to criminal actors.”

Djurovic also highlights the “direct link between pushback practices at the Hungarian border and the rise in smuggling — both in scale and in violence.”

This sentiment is shared by other rights activists such as Švabić who claims that these policies make them them completely dependent on their services — not only to attempt border crossings but also to reside in transit countries along the route, she says.

“Out of fear of pushbacks and violence, migrants are avoiding state institutions and authorities, placing their trust in smugglers, who often exploit this trust,” Švabić adds.

Role of criminal networks

The BIRN report reveals that BWK members, some reportedly holding EU-issued IDs based on protection status they were allegedly issued by Italy. According to BIRN, some of the suspected gang members may have used these documents to move seamlessly across Balkan borders, thus evading arrest. InfoMigrants approached the Italian authorities about these allegations, but they declined to comment.

Their alleged violence is, in part, enabled by state neglect and even allegations of violence and pushbacks that have been levelled at numerous authorities along the Balkan route, allegations often vehmently denied by the states concerned. For migrants themselves, there is a kind of feedback loop of trauma: asylum seekers are allegedly beaten by some authorities only to be captured by gangs once they return and then suffer similar treatment at their hands too.

Lawrence Jabs, a researcher at the University of Bologna, stated in the BIRN investigation that there is “definitely a connection between pushbacks and the hostage-taking. If you wrote it descriptively without giving any context, it would just look like the same people,” he reportedly said.

The BIRN findings highlight a broader issue in the Balkans: organized crime thrives in areas where enforcement is violent and accountability is lacking. In some cases, BWK members have reportedly infiltrated state-run refugee camps via local fixers, who allegedly tip off gang members about upcoming border crossings.

In October 2024, several suspected BWK members were arrested for abducting Turkish migrants and filming their torture. Police in Bosnia describe this extortion-based smuggling operation as “well-established and highly profitable,” with some individuals associated with BWK reportedly holding bank accounts with over 70,000 euros in deposits.

The BIRN investigation describes how one of the most notorious gangs run by Afghan migrants actually benefit from protected status in Italy. Many migration experts also emphasize that the nature of these gangs is by definition transnational.

According to Djurovic “these networks aren’t solely made up of foreign nationals. They are often connected to local criminal groups. Sometimes migrants are even smuggling drugs for others — always with local support.”

These gangs often also rely on local drivers and fixers to facilitate border crossings.

Švabić tells InfoMigrants that these groups “involve both local and refugee populations. Each person has their role.” However she notes that they have “documented people of refugee origin traveling legally in the EU to join these groups for material gain.”