This investigation reveals how Sudan’s war is being fueled by foreign weapons, drones, and military expertise from Iran, Turkey, Ukraine, and allied armed groups, despite international restrictions. The findings show that advanced systems used by the Sudanese Armed Forces require external training and support, implicating foreign advisers in a conflict marked by mass displacement and serious human rights violations.

In Depth Reports ( Khartoum – Brussels – London)

Since the escalation of the conflict in April 2023, Sudan has been plunged into a devastating humanitarian and human rights crisis. Fighting led by the Sudanese Armed Forces has resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilians and the displacement of millions, making Sudan the site of the world’s largest internal displacement crisis.

The Sudanese Armed Forces have employed a wide range of weapons in committing serious violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law—acts that, in some cases, may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

This conflict continues to be fueled by the largely unrestricted flow of weapons into Sudan from countries and companies around the world. Neighboring states are routinely used by armed groups and state actors alike as supply routes for transporting weapons into and around Sudan.

The international response—particularly that of the United Nations Security Council—has been profoundly inadequate. The current UN arms embargo is extremely limited in scope, applying only to the Darfur region, and is so poorly enforced that it has had little tangible effect in curbing the flow of weapons.

This investigation reveals the continued transfer of weapons, ammunition, and military advisers to Sudan from countries including Turkey, Iran, and Ukraine, as well as from non-state actors such as the Houthis and Lebanese Hezbollah, despite the binding arms embargo imposed by the Security Council more than two decades ago.

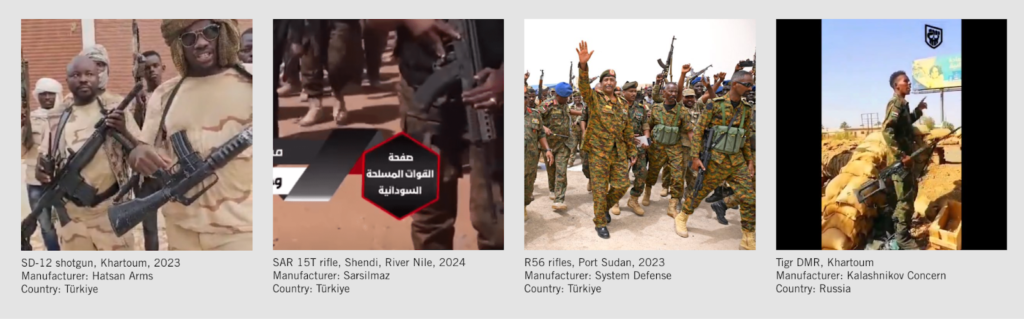

The Sudanese Armed Forces have imported large quantities of newly manufactured weapons and military equipment from these countries. In parallel, weapons and ammunition have continued to be smuggled directly into the country even after April 2023. An assessment of visual evidence indicates that these weapons have ended up directly in the hands of the Sudanese army, which stands accused of committing grave human rights violations.

According to the United Nations, more than 7.3 million people have been displaced since April 2023, bringing the total number of internally displaced persons in Sudan to over 11 million—the largest displacement crisis in the world today.

Human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have documented the Sudanese army’s use of heavy and explosive weapons in densely populated areas, actions that may constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity. Most alarmingly, this investigation shows that these violations are not being carried out solely with domestically produced weapons, but with modern arms and technologies flowing into Sudan from abroad, in direct violation of international restrictions.

Iranian Experts: Drone Operations and the Transfer of Combat Know-How

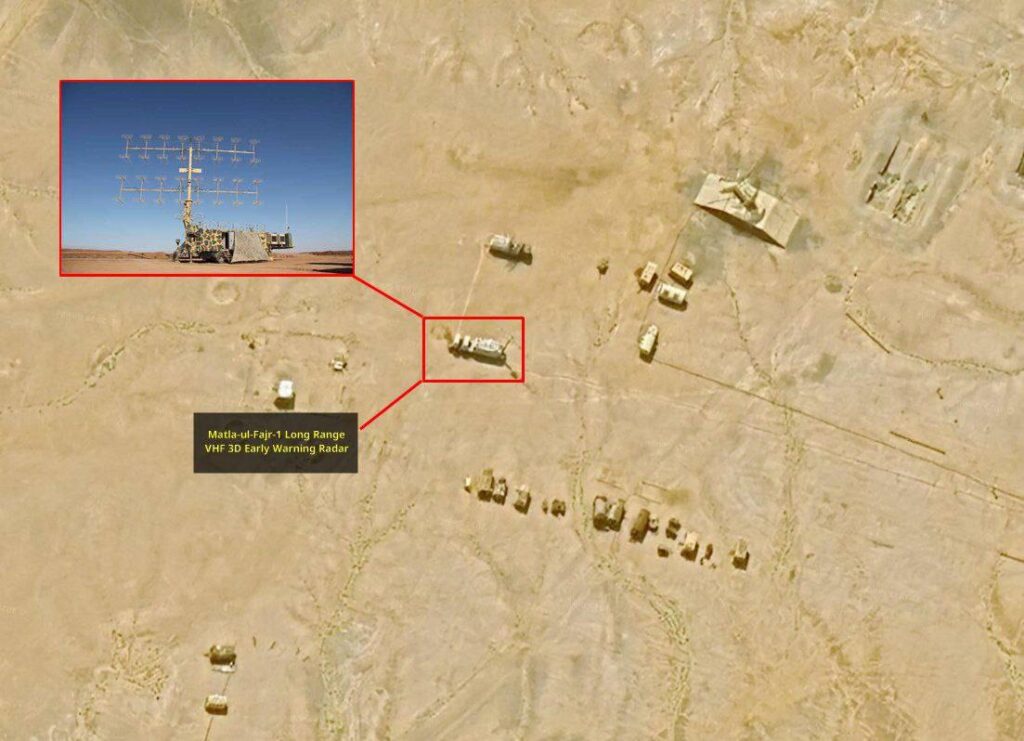

Satellite images published by Planet Labs in early January show Mohajer-6 drones and a ground control vehiclepositioned on the runway of Wadi Sayidna Air Base, a Sudanese Armed Forces–controlled facility located approximately 22 kilometers north of Khartoum.

Images show Iranian-made ground control vehicles at a Sudanese army military base near Khartoum.

Iranian support represents the most extensively documented form of foreign military assistance in the Sudanese conflict, primarily through the supply of Mohajer-6 and Ababil-series drones. The Sudanese Armed Forces are currently operating Iranian-manufactured unmanned aerial vehicles, including the Mohajer-6 and Ababil-3 models.

Over recent months, investigators have tracked the landing of Iranian cargo aircraft, including planes linked to Qeshm Fars Air, an airline affiliated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). These shipments reportedly transported drones, anti-tank missiles, advanced munitions, and radar and jamming systems.

Operating such systems requires specialized training and ongoing technical support, strongly suggesting the direct presence of Iranian experts or military advisers inside Sudan.

As the war approaches its fourth year, eyewitnesses report that Iranian weapons shipments to the Sudanese Armed Forces have continued since the earliest months of the conflict. Many of these deliveries were reportedly transferred to a mountainous site approximately 80 kilometers north of Khartoum, which hosts missile launch platforms and Iranian enrichment-related equipment.

Flight-tracking records compiled by the Dutch peace organization PAX indicate that in December 2025 and January 2026, a Boeing 747-281 cargo aircraft operated by Qeshm Fars Air conducted six flights from Iran to Port Sudan. Port Sudan is a strategic military hub for the Sudanese Armed Forces on the Red Sea coast. According to these records, the aircraft was carrying military equipment, including various types of drones.

A Boeing 747 passenger aircraft operated by the Iranian cargo airline Qeshm Fars Air arrived in Port Sudan from Bandar Abbas Airport in Iran, carrying military equipment that was delivered to the Sudanese Armed Forces.

In addition to weapons and drone shipments, converging evidence points to the presence of Iranian experts and advisers providing technical and operational support to the Sudanese Armed Forces—particularly in the operation of drones, radar systems, and electronic jamming equipment. Sudanese military sources interviewed for this investigation stated that operating systems such as the Mohajer-6 and Ababil-3 requires technical expertise that is not locally available, especially during the phases of takeoff, navigation, target selection, and integration with ground control stations.

These indicators are further reinforced by the documented presence of Iranian-manufactured ground control vehicles inside Sudanese military bases, as well as reports of undisclosed visits by Iranian military officials to Sudan since the outbreak of the war, according to testimonies from former diplomats and regional experts. Analysts believe that this role goes beyond training and includes the transfer of operational know-how, enabling the Sudanese army to deploy drones as a decisive battlefield weapon.

In this context, Mahdi Dawoud al-Khalifa, former Sudanese Minister of State at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, noted that Sudan’s military ties with Iran date back to the early 1990s but have taken on a new dimension since the start of the current war. “Strong indicators of renewed cooperation have emerged,” he said, “including reciprocal visits by military officials from both sides and undisclosed meetings.”

He added that any military cooperation with Tehran—particularly in the Red Sea region or eastern Sudan—could turn Sudan into a direct target within broader regional conflicts, especially if Sudanese territory is used to store or transit Iranian military equipment.

The escalation of Iranian military support to the Sudanese Armed Forces has also raised concerns about Tehran’s potential interest in establishing a naval base in Sudan, which would provide Iran with a strategic launch point to further threaten maritime shipping routes in the Red Sea.

With Iran-aligned Houthi forces entrenched in Yemen near the narrow Bab al-Mandab Strait at the southern entrance to the Red Sea, experts say Iran has begun paying renewed attention to Sudan and its 465-mile Red Sea coastline, viewing it as a strategically valuable extension of its regional footprint.

According to Jack Waruid, a political analyst specializing in Islamist movements, most of the Iranian weapons acquired by the Sudanese army are now under the control of factions affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which have come to possess advanced and strategic weaponry that raises serious concerns domestically as well as internationally.

An Iranian-made Mohajer-6 drone striking critical infrastructure sites in Sudan.

According to Wim Zwijnenburg, a drone expert and Head of the Humanitarian Disarmament Project at the Dutch peace organization PAX, analysis of the munitions used by Sudanese Armed Forces drones—including the engine and tail components—shows a match with the Iranian-manufactured Mohajer-6 drone. Mohajer-6 drones have been used in Sudan for several years.

To carry out this investigation into arms flows to the Sudanese Armed Forces, we relied on a multi-method research approach combining trade data analysis, digital verification of visual evidence, and fieldwork based on interviews.

Our analysis of weapons movements drew on shipping trade data from two independent sources, covering the periods 2013–2025 and 2020–2025. These datasets include all items classified under the Harmonized System customs code HS 93+, which is used globally to track small arms, ammunition, and their components. Through this analysis, we accessed detailed records of more than 1,900 weapons shipments exported to Sudan from various countries during these periods.

The shipments include handguns, rifles, man-portable rocket launchers, as well as a wide range of ammunition, while excluding combat vehicles and drones.

A snapshot of the database documenting weapons imported by the Sudanese Armed Forces.

To verify the presence and use of the weapons systems identified in the trade data, we collected and analyzed dozens of images and videos published on social media platforms, particularly X (formerly Twitter), Telegram, and Facebook.

This material included content published by the Sudanese Armed Forces, as well as propaganda footage, celebratory videos, and widely circulated content featuring known military personnel.

In addition, we conducted 11 interviews, including eight experts in the fields of security, arms trafficking, and Sudanese affairs, and nine Sudanese journalists and activists with in-depth knowledge of local dialects and weapons transport routes inside Sudan. For security and logistical reasons, all interviews were conducted remotely.

Turkey: Drones That Require Experts

At the same time, Turkey has emerged as a military supporter of the Sudanese army commander, seeking to expand its influence in Sudan through military assistance. In December, media reports indicated that the Sudanese Armed Forces received Bayraktar drones from Ankara, a development that granted General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s forces aerial superiority over the Rapid Support Forces.

Bayraktar drones possess advanced capabilities, including the ability to operate at altitudes of up to 27,000 feet and a maximum takeoff weight of approximately 650 kilograms. Manufactured by Baykar, Turkey’s Bayraktar drones are widely regarded as among the most prominent and effective unmanned aerial vehicles in the world.

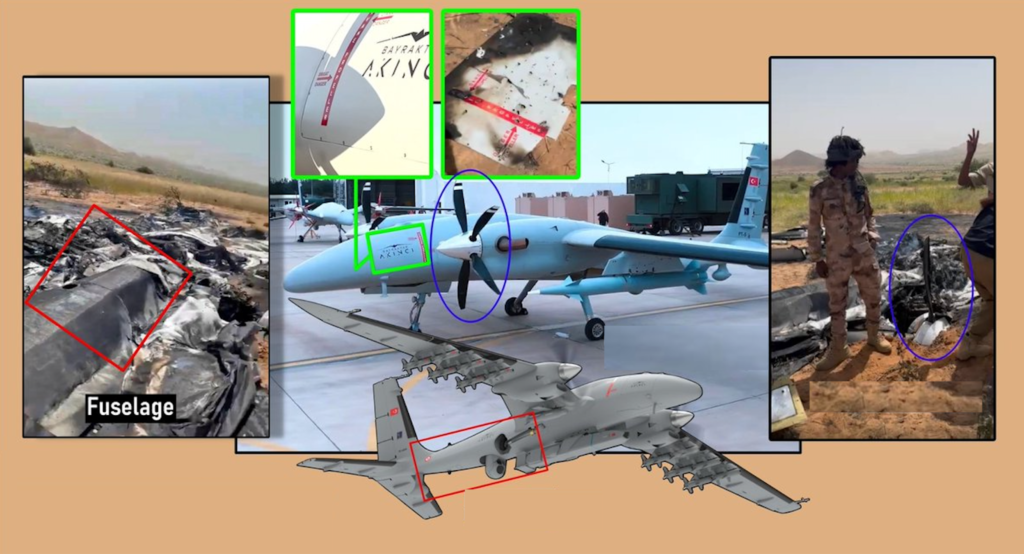

Wreckage of a Turkish-made “Akinci” combat drone— a high-altitude, long-endurance UAV—operated by the Sudanese Armed Forces.

The drone is also capable of remaining airborne for up to 27 hours, with a maximum speed of 240 kilometers per hour, and can carry a payload of approximately 1.5 metric tons.

Verified photographs and videos further document the export of Turkish-made drones to the Sudanese Armed Forces, including Bayraktar and Akinci models—specifically the Bayraktar TB2 and the Akinci, a high-altitude, long-endurance (HALE) combat drone. According to field data and verified images of wreckage, at least two Akinci drones were shot down in southern and northern Darfur.

These drones cannot be operated without specialized training, maintenance support, and advanced communications systems, reinforcing indicators of the presence of Turkish operators or military advisers, even if they are not directly participating in combat.

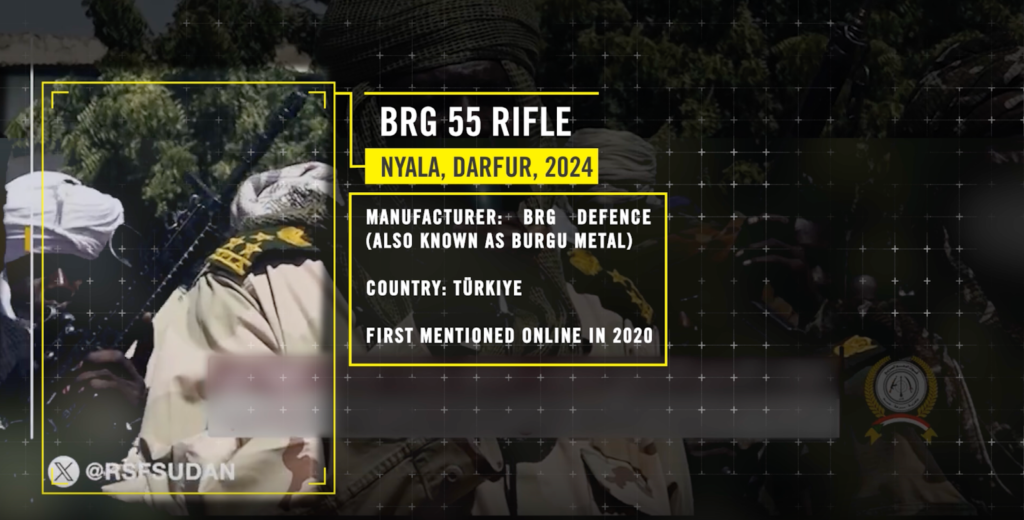

Drones are not the only Turkish weapons reaching the Sudanese Armed Forces. The BRG 55 rifle is a 5.56×45 mm assault rifle, designed in the style of the M4, and manufactured by the Turkish company BRG Defence, also known as Burgu Metal. Founded in 2013, the BRG 55 is currently the only individual weapon produced by the company.

The rifle can be identified by a large, distinctive white logo printed on the weapon’s receiver, making it visually identifiable in field imagery.

Shipping records show that these rifles were imported into Sudan through a single importer, listed in the documents as Othman Al-Tayeb Ali, who is described as being close to the Sudanese Armed Forces. The shipments were officially registered under the designation “sporting rifles”, a classification sometimes used to circumvent restrictions on the export of military weapons.

The nature of the Turkish weapons used by the Sudanese Armed Forces—particularly the Bayraktar TB2 and Akincidrones—strongly indicates the presence of operational and maintenance experts linked to the manufacturing companies or contracted on their behalf. These advanced systems do not function autonomously; they require extensive training, continuous logistical support, and the management of complex communications and data systems.

Military experts note that such support is often provided by technical advisers operating away from front lines, yet they remain a critical component of combat capability. The confirmed downing of Akinci drones in Darfur further reinforces the assessment that these platforms were deployed in advanced operational missions, implying the existence of a comprehensive human and technical support chain behind their use.

Ukrainians in Sudan’s Skies

According to senior military officers interviewed for this investigation, retired Ukrainian pilots are providing technical and training support to the Sudanese Armed Forces, particularly in the operation of aircraft and drones, amid the ongoing war led by the Sudanese army.

These accounts align with previous official statements by Ukrainian authorities. A spokesperson for Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense previously confirmed that former Ukrainian Air Force personnel are currently working as trainers in Sudan.

Edward Peterson, a former senior diplomat with extensive knowledge of Horn of Africa affairs, said: “Everything is at stake in Sudan. The situation will only become worse and more complex with the involvement of foreign powers and their logistical and military support for the Sudanese Armed Forces.”

As part of this investigation, we also documented the use of newly manufactured or externally transferred small arms and ammunition on Sudanese battlefields, including weapons routed through Yemen via the Houthi movement. The evidence shows the deployment of advanced drone-jamming devices, mortars, and anti-materiel rifles manufactured in Turkey.

Trade shipment data further indicate the export of hundreds of thousands of blank pistols to Sudan in recent years, along with millions of blank cartridges, destined for the Sudanese Armed Forces. Amnesty International believes that these items are being widely converted into lethal weapons inside Sudan, raising serious concerns about arms diversion and misuse.

The Houthis: Smuggling Expertise and Shadow Advisers

The Houthi presence in Sudan dates back to 2001, rooted in the relationship that linked Iran to the Sudanese regime at the time. This relationship later evolved as part of the Houthis’ efforts to build external networks that could secure funding and weapons.

Following the outbreak of fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces, Khartoum restored relations with Tehran after an almost eight-year rupture, seeking to circumvent the international arms embargo imposed on Sudan.

Within this context, Iran began supplying weapons to the Sudanese army through Houthi networks, which possess extensive experience in land and maritime arms smuggling. Western reports, including investigations by Bloomberg, have indicated that Tehran has been seeking to establish a foothold on the Red Sea, including attempts to create a permanent naval base to sustain long-term support for the Houthis.

Evidence suggests the presence of Houthi fighters involved in combat inside Sudan, though the group’s primary interest lies in maintaining influence along the Red Sea corridor—linking the Sudanese conflict to the war in Yemen within a broader Iran-led regional alliance network.

The Houthi role in Sudan is not limited to arms smuggling routes. Western sources also point to the presence of Houthi experts providing logistical and technical support, drawing on their longstanding experience in operating drones and smuggling weapons across the Red Sea.

The Houthi movement is regarded as one of the most experienced actors in asymmetric warfare and the use of low-cost drones. Over years of conflict in Yemen, it has developed complex networks for smuggling, operation, and storage. According to security experts, this expertise positions the Houthis as a practical conduit for transferring Iranian technology and adapting it to the Sudanese context, even in the absence of official declarations or a visible on-the-ground presence.

Hezbollah: Indirect Networks

Experts on armed groups note that Lebanon’s Hezbollah forms part of Iran’s transnational expertise network, particularly in areas of irregular warfare training and the operation of advanced weapons systems.

According to these experts, Hezbollah operatives have traveled to Sudan to train the Sudanese Armed Forces in the use of drones, especially in operational aspects. They are reportedly stationed at military bases near Port Sudan, a strategically significant area on the Red Sea coast.

Historically, during the rule of former president Omar al-Bashir, Sudan served as a logistical corridor for networks linked to Iran and Hezbollah, a role that has raised renewed concerns about the reactivation of these channels—whether for arms transfers or the exchange of military expertise.

These findings indicate that the conflict in Sudan is no longer driven by weapons alone, but by a complex web of foreign experts and advisers who transfer knowledge, operate advanced technologies, and reshape the balance of power. In the absence of effective international oversight, these networks have become a key factor in prolonging the war and deepening civilian suffering.