This investigation uncovers a covert network that recruits retired Colombian soldiers into Sudan’s war. Drawn in by false promises of security jobs, they are flown to Port Sudan, given brief training, and then integrated into Sudanese army units deployed to the frontlines in Darfur and Kordofan.

Testimonies from civilians and soldiers reveal how Spanish-speaking mercenaries spread fear, resentment, and leave behind unmarked graves. For Colombian families, the remittances mean survival; for Sudan’s army, these fighters are a desperate fix that further erodes its legitimacy.

By the Investigative Team: Fathi Ahmed (Khartoum), Juan Alvarez (Bogotá), Camila Torres (Medellín).

The phenomenon of mercenaries, or military contractors, has witnessed a striking surge over the past two decades, evolving from scattered individual cases into a cross-border industry producing auxiliary armies or small units carrying out precise combat and security missions. At the heart of this rise, Colombia has emerged as one of the key human reservoirs feeding this global market.

From Haiti, where they were implicated in the assassination of the president, to Ukraine, which welcomed some of them to its battlefronts, and all the way to Sudan, where they now take part in a bloody, protracted conflict these professional fighters have left their mark on some of the world’s most volatile flashpoints.

Despite the differing geographies and actors of these wars, the motives remain similar: the pursuit of better economic conditions in the face of poverty back home in Colombia, even if the price means fighting in wars whose maps and causes they barely understand.

In the neighborhoods of Omdurman, Sudan, the scene was no different. Civilians recounted how they encountered strange men speaking Spanish with a distinct Colombian accent, fighting within Sudanese army units. Testimonies from Sudanese soldiers confirmed the same: Colombian mercenaries had become part of the war.

But how did soldiers from Latin America end up in the heart of a bloody African conflict?

A few months ago, mysterious advertisements appeared on the streets of Bogotá and Medellín: “Well-paid security jobs in the Middle East – official contracts – salaries in US dollars.”

The ads did not specify the workplace or the nature of the tasks. Still, the promise was enough to lure hundreds of demobilized Colombian soldiers, veterans of counterinsurgency units and internal guerrilla warfare, who were searching for new opportunities after years of service.

Alongside these ads, unusual flight patterns were observed groups departing Colombia through transit hubs and eventually landing in military airports in eastern Sudan, most notably Port Sudan.

Among those who arrived was Carlos Jefany, a former Colombian army soldier who had retired early. He recounted his story to our team after managing to escape Sudan and return to his country:

“A retired officer approached me and offered a contract with a private company. He said the job was protecting oil facilities in the Middle East, with a salary of up to $3,000 a month. That’s a huge sum for us. Many of my comrades agreed immediately.”

But what he later discovered was that the destination was not oil fields in Libya, as rumored among the recruits, but Sudan. There, he and his colleagues were met with a very different reality: training camps, bloody frontlines, and a war whose causes they did not even know.

A Systematic Military Integration

Arriving in Port Sudan was not the end of the journey for the Colombian fighters, it was merely the beginning. After long hours of travel through multiple transit points, they found themselves on the tarmac of a military airbase under tight security.

There, they were received by special Sudanese units and immediately transported in windowless military buses to Wadi Sayyidna Camp north of Khartoum.

Inside the camp, the foreign recruits underwent an intensive training course that lasted a few weeks. One Sudanese officer involved in overseeing the process told our investigation team:

“The goal was not to teach them how to fight; they were already professional soldiers. What we focused on was familiarizing them with local weapons, particularly Kalashnikovs and light artillery, and with movement tactics in an open desert environment, which is very different from the jungles they were used to in Colombia.”

The training also included lessons on local customs and basic Arabic commands words like right, left, fire, stop to facilitate field coordination with Sudanese troops.

After the Wadi Sayyidna phase, some of the mercenaries were transferred to al-Merikhiyat Camp near Khartoum, where they trained in urban warfare and night raids.

At the end of the training period, the Colombian mercenaries were deployed to the hottest frontlines, particularly in the states of Darfur and Kordofan.

Carlos Jefany, who had served 12 years in the Colombian army before being recruited to Sudan, recounted his experience to our team:

“We were integrated into small assault units between ten and fifteen fighters within larger battalions. Our main task was to carry out direct attacks and storm fortified positions.”

Beyond their combat role, the Colombian mercenaries had a double-edged psychological impact within the Sudanese army. For the military leadership in Khartoum, their presence was seen as a way to boost the morale of exhausted soldiers worn down by a long and grueling war.

As Jefany put it: “The local soldiers looked at us as a professional fighting force that did not fear death.”

But their presence was not free of tension. Some Sudanese soldiers felt threatened and discriminated against, perceiving that the Colombians were treated with financial and logistical privileges far exceeding what they themselves received.

Civilian Testimonies – Fear of Strangers

The sight of Colombian mercenaries was not a fleeting scene in Sudanese memory, but a collective shock retold in camps, markets, and bombed-out homes alike.

In the city of Nyala, Darfur, Aisha a woman in her fifties who fled with her five children after their neighborhood was stormed recounted the terrifying moment:

“When the army forces entered our area, it wasn’t normal. I heard voices in languages I couldn’t understand, but one word kept repeating: Colombia… Colombia. I saw a huge man in a military uniform with a patch in yellow, blue, and red. That’s when I realized we were facing foreign fighters.”

She added: “The children were terrified. It no longer felt like we were surrounded by a Sudanese army, but by strangers who had come from far away.”

In the alleys of Kordofan, another civilian described the encounter with anger in his voice:

“I was certain these men were neither Arabs nor Africans. It was shocking… we are not just fighting a national army, but strangers brought from another continent. That destroys any sense of belonging or justice.”

The presence of fighters speaking Spanish in the heart of Sudanese towns deepened residents’ feelings of alienation and estrangement. Some avoided leaving their homes out of fear of clashing with these outsiders, while others spoke of a sense of humiliation as if their land had been turned into an open battlefield for whoever could pay to import soldiers.

Mahmoud, a young man displaced to a temporary camp, put it this way: “War is harsh enough when it’s between people of the same country. But when you face men whose language you don’t understand, whose identities and reasons for fighting you don’t know… the fear doubles. It feels as if this is no longer our homeland.”

Unidentified Bodies

The testimonies did not come only from civilians or fleeing mercenaries; they also reached the corridors of the Sudanese army itself, where accounts began to leak, exposing the contradictions created by integrating foreign fighters into its units.

In an off-the-record conversation with a local journalist, a former officer in Sudan’s General Staff hinted at “a state of confusion within some military units due to the presence of bodies that were never handed over to families and whose identities do not match Sudanese army records.” He added: “Names of the dead have been entered that no one can identify.” This further supports the hypothesis that foreign fighters were secretly folded into the Sudanese army’s ranks.

This aligns with the testimony of Juan David, the brother of a Colombian soldier killed in Sudan in late August. He says: “Before he was killed, my brother told us that five of his comrades had fallen in battle and that their bodies were never repatriated to Colombia. The Sudanese army buried them there as if they never existed. To this day, we don’t know where he was laid to rest. His wife still waits anxiously for his remains to be brought home, but to no avail. The painful truth is that my brother and his companions ended up as mere numbers in a war that isn’t theirs.”

These testimonies coming from the heart of both the military and civilian spheres reveal a dilemma far deeper than the mere presence of mercenaries on a battlefield. They expose a human price paid in blood, and soldiers erase the moment they fall, leaving behind families trapped between the silence of fear and the impossible hope of return.

In Colombia, the issue of mercenaries killed in Sudan alongside the Sudanese army, without the return of their remains, has sparked public outrage. In parallel, lawyers and human rights advocates are pursuing the matter with mounting concern, amid questions about the fate of fighters who fell in battle and were buried without any official notification to their families.

Gustavo Juan Ramírez, a Colombian attorney working with victims’ families to recover their loved ones’ remains, says: “What’s happening is tragic. Entire families are waiting to bury their sons with dignity, but the truth is that many were left in Sudan without a trace. This is not only a violation of international law it is a deep human wound that multiplies the suffering of mothers and wives who don’t even have a grave to visit.”

A member of the Colombian Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee, who requested anonymity, told the investigation team: “Leaving our citizens’ bodies on a foreign battlefield, without identity and without consular care, is legally and morally unacceptable. We demand that the government issue a public position, activate repatriation mechanisms under international law, and pursue the recruitment networks that deceived these young men with misleading contracts.”

He added: “Many families have contacted me, and all they ask for is the right to bury their sons with dignity. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Migración Colombia, and the Attorney General’s Office must act immediately, in coordination with Sudanese authorities, to locate burial sites and repatriate remains or at least provide official documents clarifying the circumstances and location of death.”

The investigation team contacted the following Colombian authorities via official email the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Defense, the Attorney General’s Office, Migración Colombia, and the regulator of private security companies requesting an official comment on information concerning the recruitment and transfer of Colombian nationals to fight in Sudan within Sudanese army units. As of publication time, no response had been received.

Why Does the Sudanese Army Turn to Mercenaries?

In the heart of Khartoum, the Sudanese army faces a multifaceted crisis: continuous human losses, internal defections, political isolation, and a suffocating economic blockade. Taken together, these factors have pushed its leadership to seek urgent solutions to compensate for the growing depletion in its ranks.

Since the outbreak of the latest internal conflict, the army has lost thousands of soldiers either killed, captured, or defecting to the Rapid Support Forces. With exhaustion mounting after years of civil wars, the military institution has become incapable of sustaining its battlefield momentum.

Under such conditions, turning to foreign mercenaries chief among them Colombians emerged as an attractive option. Most Colombian soldiers previously served in counterinsurgency units and in guerrilla warfare against the FARC and drug cartels, giving them hands-on experience in unconventional combat. Added to this is the fact that thousands of soldiers are discharged in Colombia every year without viable economic alternatives, making them easy prey for recruitment networks.

Colombian researcher Jorge Mania summarizes the phenomenon: “The Colombian soldier is trained for unconventional warfare. More importantly, he is low-cost compared to Western soldiers. Thousands leave the army each year whether due to retirement or low wages which makes them easy targets for recruitment networks.”

Beyond the military and economic dimensions, Sudan is also grappling with diplomatic isolation that prevents it from obtaining official backing from major powers. The United States and the European Union have imposed strict restrictions, while some Arab states are reluctant to provide overt support. Within this context, the option of Colombian mercenaries becomes an “unofficial” way to plug the gaps without sparking international uproar.

The decision also carries a psychological element. Sudanese officers saw the presence of mercenaries as a way to lift the morale of weary soldiers. One officer told the investigation team: “Having Colombians with us gives the impression that we are not alone in this war that others trust us and fight alongside us. It’s a message to the soldiers and to the enemy alike.”

Yet, not all experts see this as sustainable. Dr. Andreas Krieg, a scholar of security and defense studies, warns: “Turning to mercenaries is not just a short-term military decision; it reflects a deeper crisis. When an army can no longer recruit local fighters, it resorts to renting an external force. That undermines its legitimacy more than it strengthens it.”

Money Buys Everything… Even Men

The phenomenon of “soldiers for hire” is not new in Colombia. It is the extension of a long trajectory that has turned the country into an open market for exporting fighters driven by intertwined economic, social, and military factors.

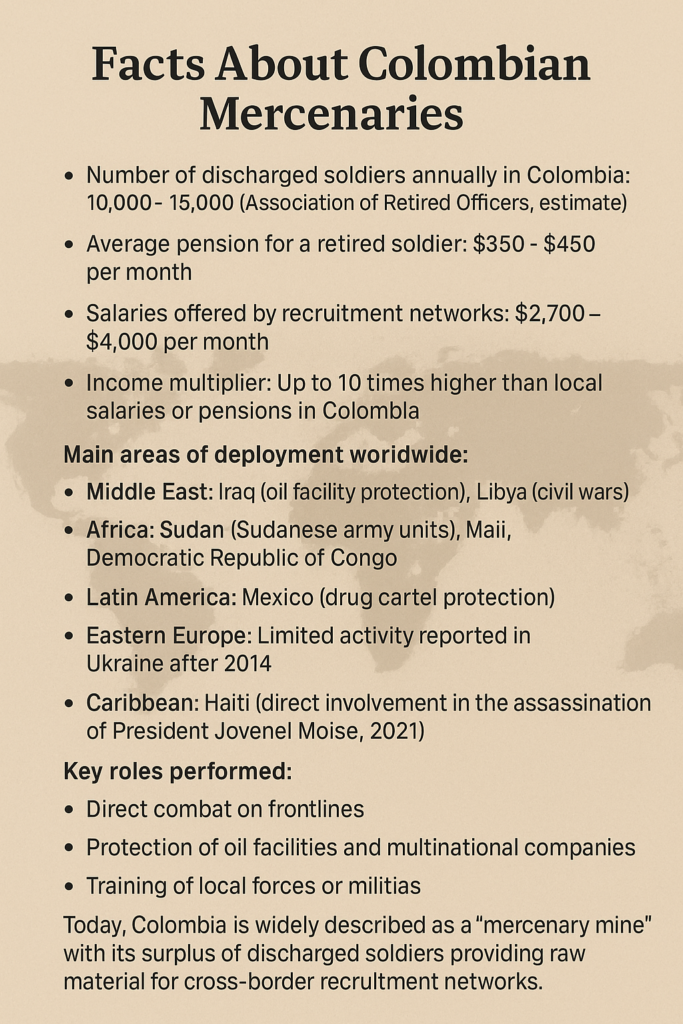

According to estimates by Colonel John Marulanda, president of the Association of Retired Officers of the Colombian Armed Forces, between 10,000 and 15,000 soldiers and officers retire or are discharged each year. Most of them find themselves without real economic alternatives, in a country plagued by high unemployment and limited opportunities in the civilian sector.

This gap opens the door wide to recruitment networks: a retired soldier can multiply his income nearly tenfold simply by signing a contract with a private security company even if it means joining foreign conflicts whose context he does not know.

This financial disparity has turned Colombia into what experts describe as an “inexhaustible mine” of mercenaries. There is always a steady supply of trained soldiers, willing to risk their lives in exchange for an income that guarantees their families a better standard of living.

In addition, the Colombian army’s long history in guerrilla wars and counterinsurgency has made its veterans prime targets for international mercenary networks. They bring with them:

● The ability to fight in complex environments (jungles, mountains, densely populated cities).

● Skills in ambushes, field intelligence, and unconventional tactics.

● Military discipline forged through decades of war against the FARC and the cartels.

This is why their presence has not been limited to Sudan alone. They previously joined frontlines in Iraq and Libya, where they were used to protect oil installations and, at times, for direct combat. In Haiti (2021), dozens of Colombian mercenaries were implicated in the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse one of the most shocking scandals in the history of “exported soldiers.” In Africa, they have been spotted in Mali and the Democratic Republic of Congo, operating within private security companies.

Today, this is no longer about individual soldiers seeking work contracts. It has evolved into an organized industryinvolving private security firms, middlemen, and transnational financing networks. Some of these companies are legally registered in Colombia or Panama, yet they operate as fronts for mercenary contracts managed in secrecy.

As Colombian researcher María Teresa Ruiz, a specialist in Latin American conflicts, explains: “Colombia produces what can be called cheap military labor. The Colombian soldier leaves service with unparalleled combat experience, but with no economic future. This combination makes them an ideal resource for mercenary networks.”

A Violation of the United Nations Convention

The presence of Colombian mercenaries in Sudan cannot be viewed merely as a military or economic phenomenon; it is a clear violation of international law. The United Nations International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries, adopted in 1989 and ratified by dozens of countries, provides a precise definition of a mercenary and criminalizes:

● The recruitment, use, financing, or training of mercenaries.

● Direct participation in hostilities within a country to which they do not belong.

● Gaining material or political benefit from their services in internal or international conflicts.

In this sense, bringing Colombian fighters to serve in the Sudanese army against local forces constitutes an explicit breach of the Convention.

Yet, the reality is far more complex. Much of this activity takes place under the cover of private security companies, which present contracts in vague terms such as “facility protection” or “security services” while the true purpose is direct participation in combat.

Professor Antonio Cassese, an international law expert at the University of Geneva, explains the dilemma:

“Despite the clarity of the UN Convention against the recruitment of mercenaries, the loophole lies in private security companies. They provide a legal cover for their activities, making it difficult to prove the intent of direct combat involvement.”

He adds: “Nevertheless, bringing Colombian fighters to serve in the Sudanese army against local forces clearly falls within the scope of international criminalization.”

The use of mercenaries complicates Sudan’s image before the international community and places the war-torn country under international scrutiny whether in the Human Rights Council or before the International Criminal Court, which has already examined cases involving the use of foreign forces in domestic conflicts.

Sudanese lawyer Abdullah al-Tayeb notes: “Even if the international community fails to hold the Sudanese government directly accountable, exposing these recruitment operations can lead to additional sanctions on the officers involved, and potentially on intermediary companies in Colombia or abroad.”

Silent Families in Colombia

Behind every mercenary who leaves Colombia for the battlefields of Sudan, a family remains suspended between hope and fear: hope in the money their sons send home, and fear that a temporary absence could turn into a permanent loss.

Our team in Medellín tried to reach the families of several recruits who had recently departed. Most, however, refused to speak. Their hesitation stemmed not only from fear of losing the financial support their sons provided, but also from the threat of retaliation by recruitment networks that enforce a collective silence on families.

A relative of one young mercenary told us cautiously: “Even if we wanted to talk, what would happen if the intermediaries found out? Money is being sent, commitments are being met. Speaking could cut off the family’s income.”

Still, one mother agreed to break her silence. Sitting in a small room on the outskirts of Medellín, surrounded by her children’s photos on the wall, she spoke softly: “My son told me he was going to work for a security company in Libya. I thought he would be guarding buildings or oil facilities. The last time we spoke, he told me he was in Sudan. I didn’t even know where Sudan was. I don’t know when he will return… the money matters, but I’m terrified I may never see him again.”

For these families, remittances sometimes as much as $3,000 a month can mean the difference between crushing poverty and a more stable life. In a country like Colombia, where poor neighborhoods are plagued by unemployment, violence, and lack of opportunity, a mercenary contract feels like an economic lifeline, even if it is, in truth, often a death sentence.

This family silence goes beyond personal fear; it reflects a complex social fabric. In some Colombian communities, mercenaries are not portrayed as hired guns killing in foreign lands, but as “heroes” bringing money to their households. This narrative makes families even more cautious about speaking openly about what their sons are actually doing, adding yet another layer of silent complicity that shields recruitment networks.

Today, Colombia is widely described as a “mercenary mine” with its surplus of discharged soldiers providing raw material for cross-border recruitment networks.

A War with Strange Faces

What this investigation has revealed is not merely the details of secret flights or disguised contracts, but an entire system that exports poverty from Colombia to the battlefields of Sudan.

From intermediaries in Medellín distributing contracts, to officers in Khartoum moving fighters to the frontlines, the threads intertwine into an international network that violates laws and disregards human lives.

In Sudan where the war should ostensibly be a domestic matter battles are now fought with foreign voices and unfamiliar accents, a scene that encapsulates the violence itself.

In Colombia, the cycle of poverty and marginalization continues to push retired soldiers into the arms of these networks, turning their bodies into cheap commodities in a global market for war.

The outcome is the same: Sudanese civilians feeling estranged in their own homes before fighters whose language they cannot understand, and Colombian families waiting without certainty for the return of their sons caught between the hope of money and the fear of death.

And so the question remains: will mercenaries continue to be treated as mere “hired guns” in the wars of others, or will exposing these networks one day lead to real accountability restoring dignity to the victims, whether in the burning streets of Khartoum or the impoverished neighborhoods of Bogotá?